I've had this article sitting in my drafts since 2022. But recently, a friend reached out asking about using NestJS for their new projects, and I realized I needed to at least publish this draft so they don't make the mistake of choosing it. Consider this my unofficial warning letter to the world.

NestJS often presents itself as a great framework for teams new to the TypeScript/JavaScript ecosystem that hope to quickly get up to speed, offering a structured and opinionated approach that stands out from alternative frameworks using Node.js. It also can feel attractive to engineers with experience with Angular, due to its apparent similarity, as it also makes use of Dependency Injection (DI), decorators, and classes.

Yet, this seeming familiarity, together with documentation that only ever presents the happy paths, can lead inexperienced teams into a painful journey of pitfalls and footguns.

As much as this article is about pointing out NestJS's flaws, I have mad respect for the people working on this project, and I'm aware it's powering thousands of services around the world. The goal of this article is simply to highlight its pitfalls for people to know what they are getting into and avoid these beginner mistakes.

Danger #1: A flawed setup

The strictNullChecks trap

When setting up a NestJS project using the Nest CLI, everything is prepared for you: first module, tests, ESLint, gitignore, tsconfig...

And that's super nice! So now let's add Prisma, following the documentation, and start writing our own code! If you want to see the details, here is a link to the repo. I also created a branch per example if you want to follow along.

Let's build an /og endpoint that gives back our first user's name when hit:

// App Controller

@Controller()

export class AppController {

constructor(private readonly appService: AppService) {}

@Get('/og')

async getHello(): Promise<string> {

return await this.appService.getFirstUserName()

}

}

// App Service

@Injectable()

export class AppService {

constructor(private readonly prisma: PrismaService) {}

async getFirstUserName(): Promise<string> {

const user = await this.prisma.users.findFirst()

return user.email

}

}Congratulations, we just built our first endpoint 🎉

Also, congratulations, we just wrote our first bug 💀

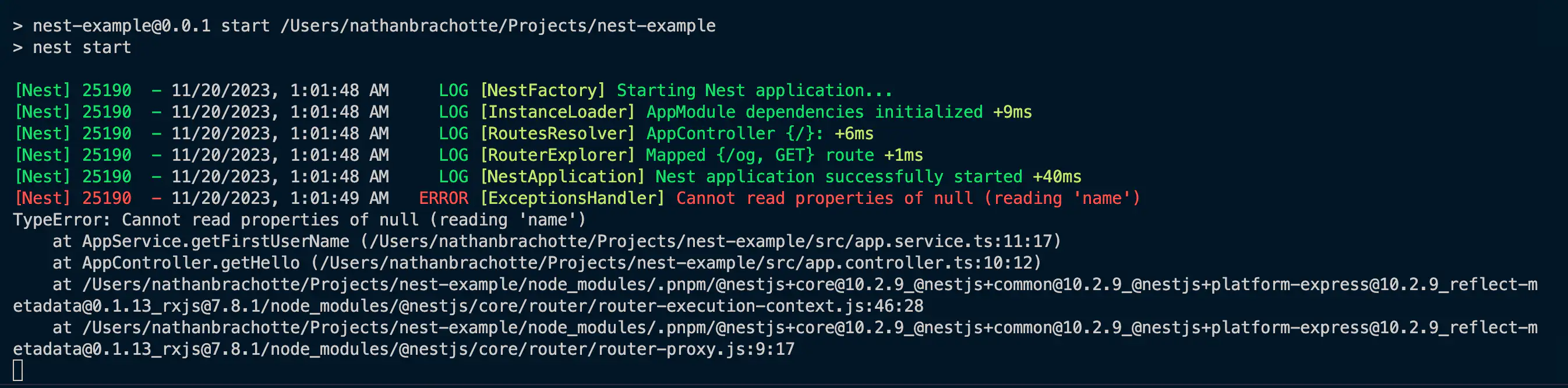

If we try hitting the /og endpoint on an empty users table:

And Nest will return:

{

"statusCode": 500,

"message": "Internal server error"

}So how did this happen?

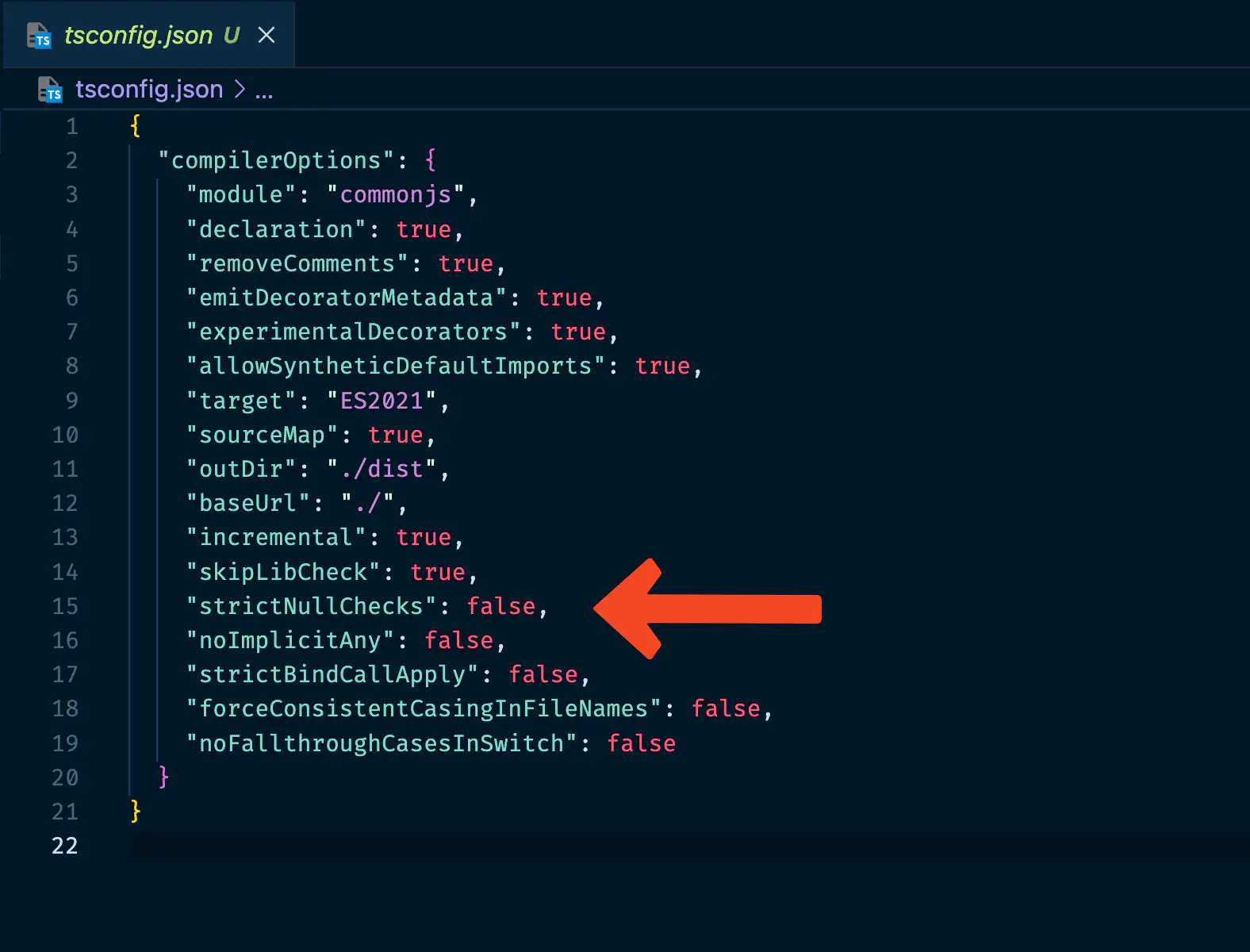

Well, as it turns out, if you look into the tsconfig that NestJS generated out of the box:

strictNullChecks: false here means that for any method like this:

async getHiMessage(): string | null {

if (Math.random() > 0.5) {

return 'Hi mom'

}

return null

}We actually will only get string as a return type:

const hiMessageDefinitelyAString = getHiMessage()

// ^ string (should be string | null!)

const toDad = hiMessageDefinitelyAString.replace('mom', 'dad') // 💣 KaboomThis also applies to undefined. Your entire codebase becomes a minefield of

potential null reference errors.

Now this sounds like it's a pretty easy problem to catch, no? Well, I'd think so too, but as it turns out, both of the NestJS projects I joined in my career—bootstrapped by engineers new to the TypeScript ecosystem—didn't catch this right away. And although both projects were pretty early on, the teams had still been writing hundreds of lines of code already without realizing their mistake.

That meant we had to update the tsconfig and handle technical debt, although the projects were only a few months old! Not the start you want when you're a startup.

The fix: Strict TypeScript config

Type strictness should be much higher when starting in a new codebase. Here is my proposal:

{

"compilerOptions": {

"strict": true,

"strictNullChecks": true,

"noImplicitAny": true,

"noImplicitReturns": true,

"noFallthroughCasesInSwitch": true,

"noUncheckedIndexedAccess": true,

"forceConsistentCasingInFileNames": true,

"exactOptionalPropertyTypes": true

}

}Now, with this new tsconfig, you'll be forced to handle all cases from Prisma types:

async getFirstUserName(): Promise<string> {

const user = await this.prisma.user.findFirst()

if (!user || !user.name) {

throw new NotFoundException('User name not found')

}

return user.name

}Oof, much safer. We can breathe now.

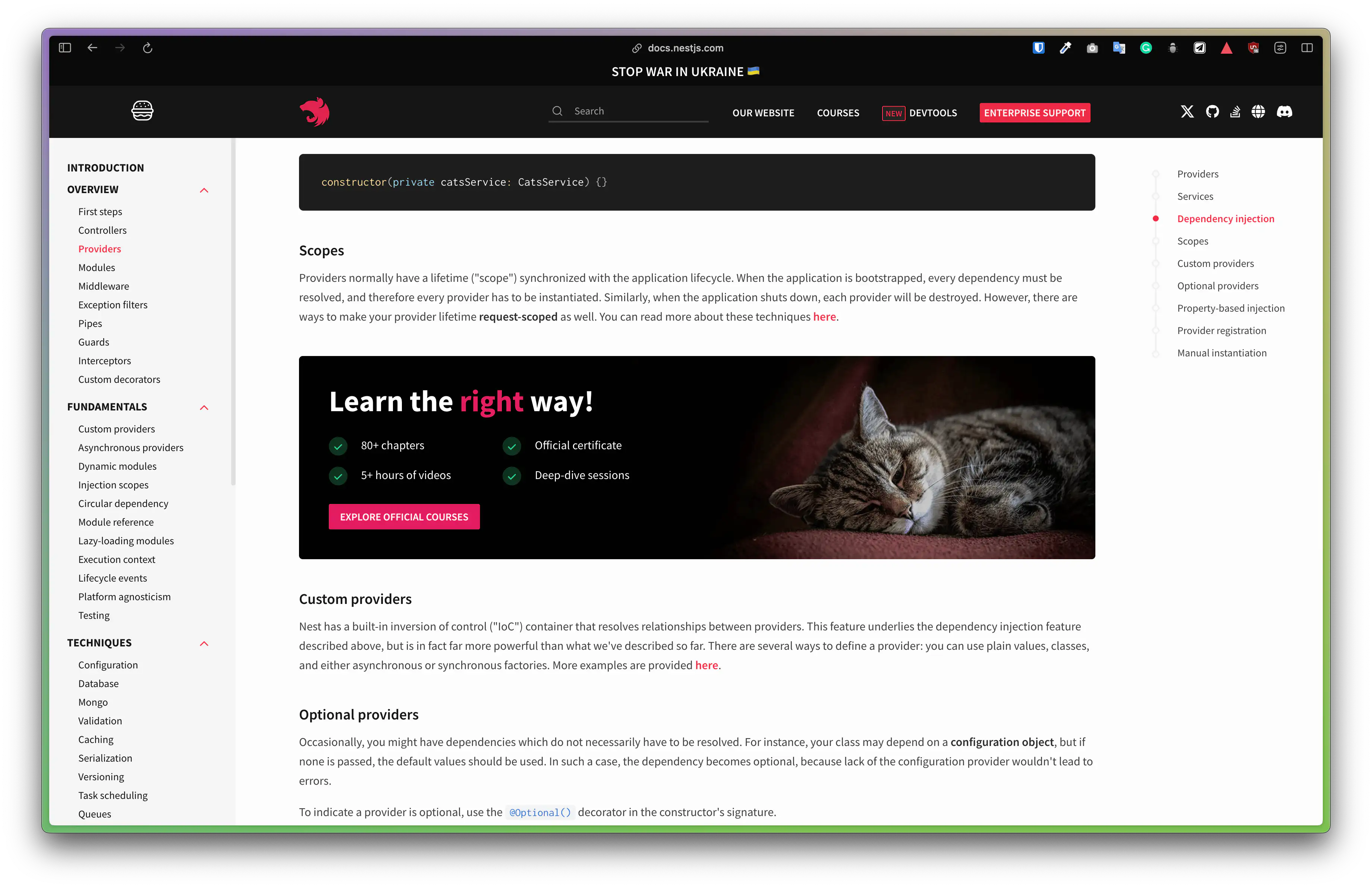

Danger #2: Documentation as an upselling strategy

Let's admit it, I'm a spoiled engineer. I've always gotten to work with the nicest frameworks out there, and they always had quite outstanding documentation: React, React Native, Next.js, and even the uglier but still pretty good ExpressJS docs.

NestJS's documentation does look and feel pretty nice when looking around the first time and doing the due diligence as to whether this would be a good framework for a company to build with. But from experience, it can be pretty light on explanations. Most pages show you the very basic happy path to a solution, but usually don't mention the gotchas and the problems that are likely to come your way.

Unlike documentation like React's that takes the time to present new hooks, but also takes the time to explain when you should or should not use them, what causes errors to show up—all before you even try them! In NestJS, this is not the case.

You might wonder why?

This lack of depth in the documentation could potentially be linked to the NestJS course offered by its author—that is shown on almost every page of the documentation, in the middle of the content!

That's quite an interesting way to convince users to get the paid course for more comprehensive guidance.

Did someone say conflict of interest?

Don't get me wrong, the people who built NestJS definitely deserve their weight in gold for the amount of work they put into this project. There has for a while been a funding problem in OSS.

But I feel deceiving users into thinking things are straightforward without giving more detailed documentation—while at the same time selling and promoting your own course in the docs—isn't the way to go about it.

Even NestJS's Twitter presence is basically about retweeting people who bought the course. Does the NestJS team have any incentive to proactively make the docs more exhaustive and comprehensive when the money they make from the framework is from tutorials?

Danger #3: Data Flow - GLHF

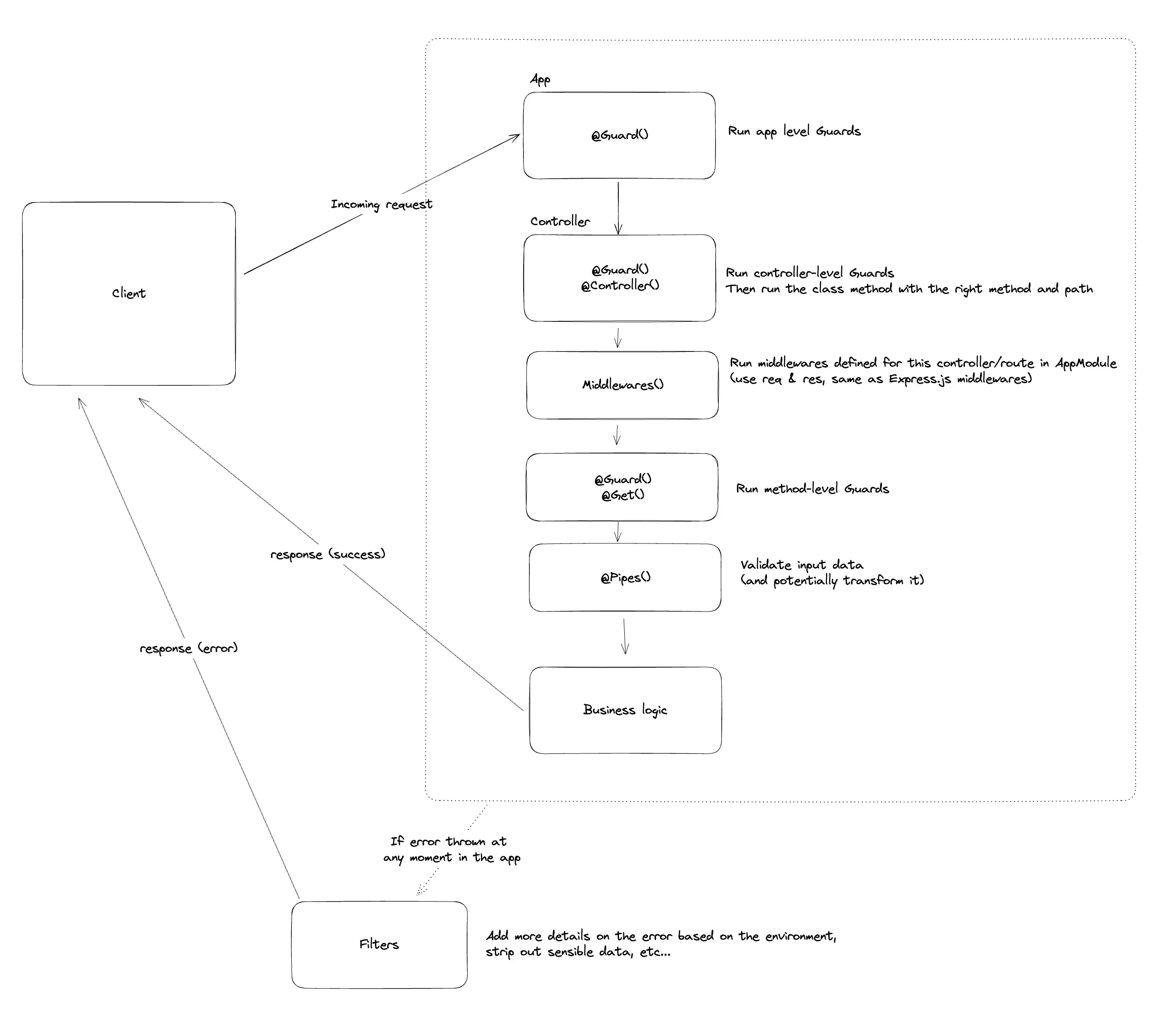

NestJS's architecture follows a specific data flow, utilizing concepts such as Middlewares, Guards, Interceptors, Pipes, Validators, Entities, and Data Transfer Objects (DTOs). A crucial aspect of this flow is understanding how validation works both at the entry and exit points of the backend.

These components are explained one-by-one in the documentation, but it can be hard to group them together and understand how they interact.

I wrote a whole separate article about the NestJS request lifecycle if you want to deep dive into the execution order of these components.

Here's my take on the overall data flow:

The danger here isn't necessarily inherent to NestJS, but the documentation doesn't do a great job at explaining in which order each component runs, or what happens when things go wrong.

Interceptors introduce RxJS complexity

One thing worth mentioning: when you start using Interceptors, you're suddenly introducing RxJS and Observables to your codebase. This is a whole paradigm shift that can confuse teams unfamiliar with reactive programming.

Guards and their cryptic typing

Guards are powerful for authentication and authorization, but typing the context properly is poorly documented:

// How do you correctly type this?

const request = context.switchToHttp().getRequest()

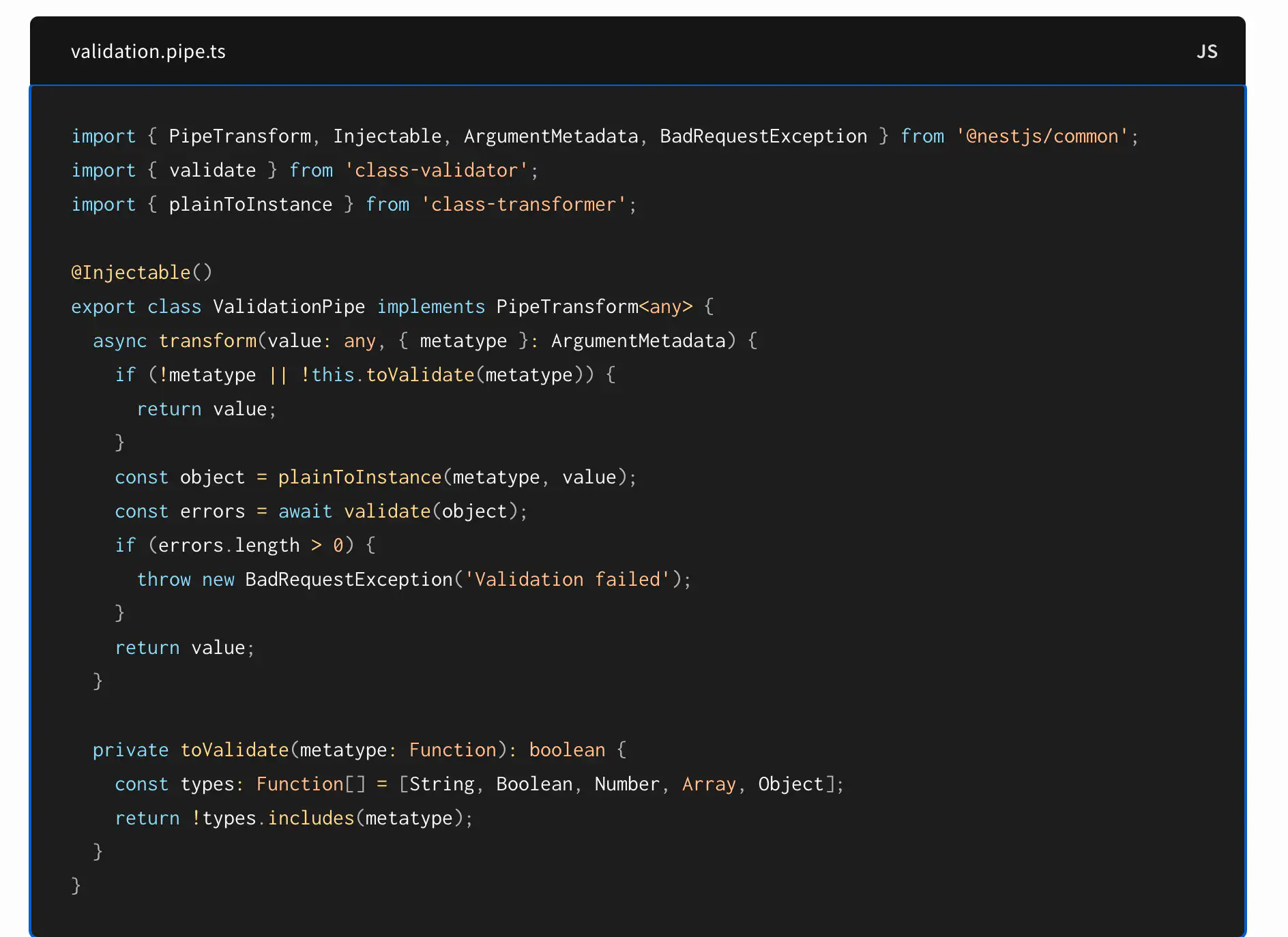

// What type is request? The docs don't tell you clearly.Pipes and validation confusion

Even the official validation pipe example from the docs is riddled with any:

The transform method takes value: any and returns... any. Even after validation succeeds, you don't get a typed object back. The metatype is typed as Function. This is the official documentation teaching you to bypass TypeScript entirely.

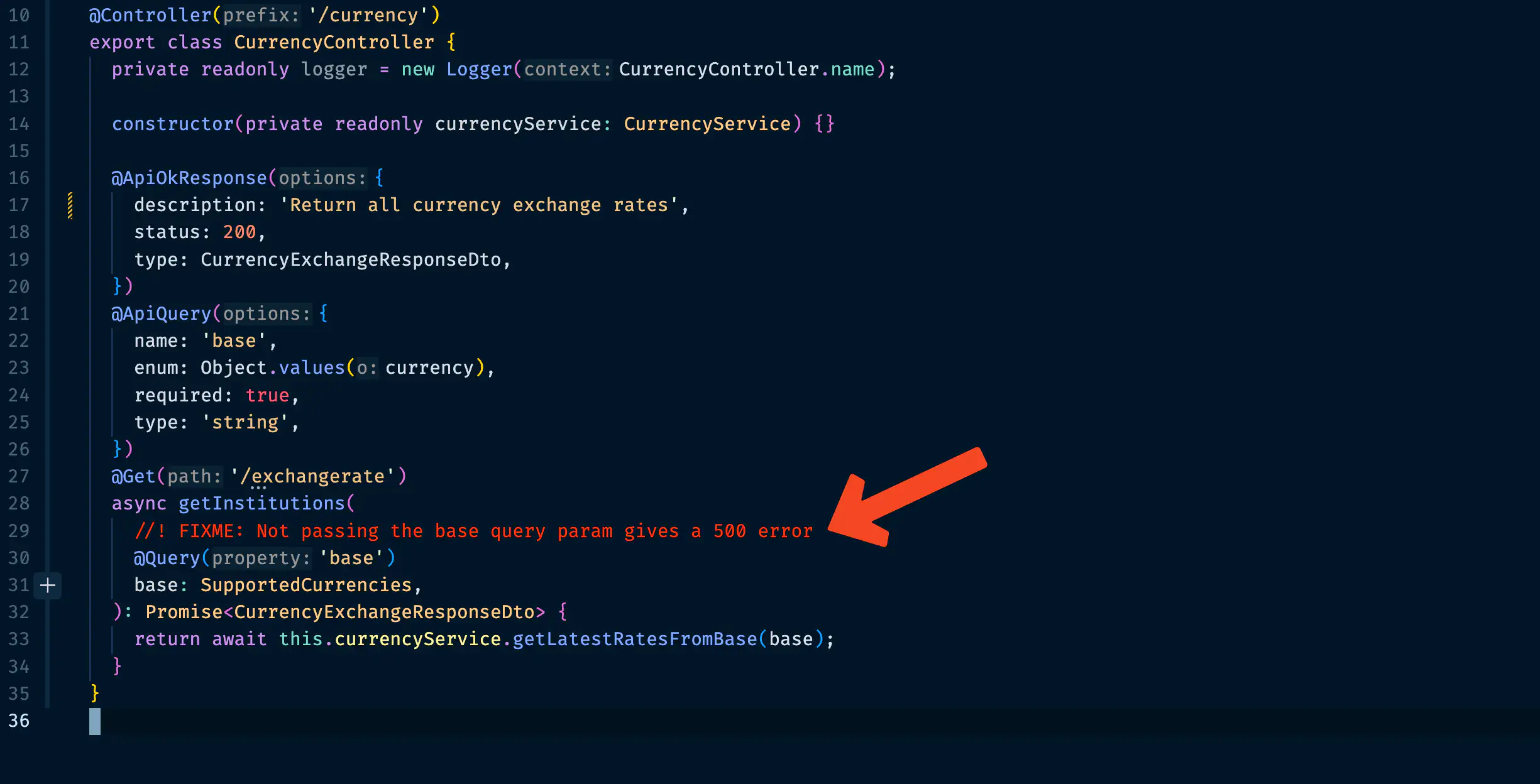

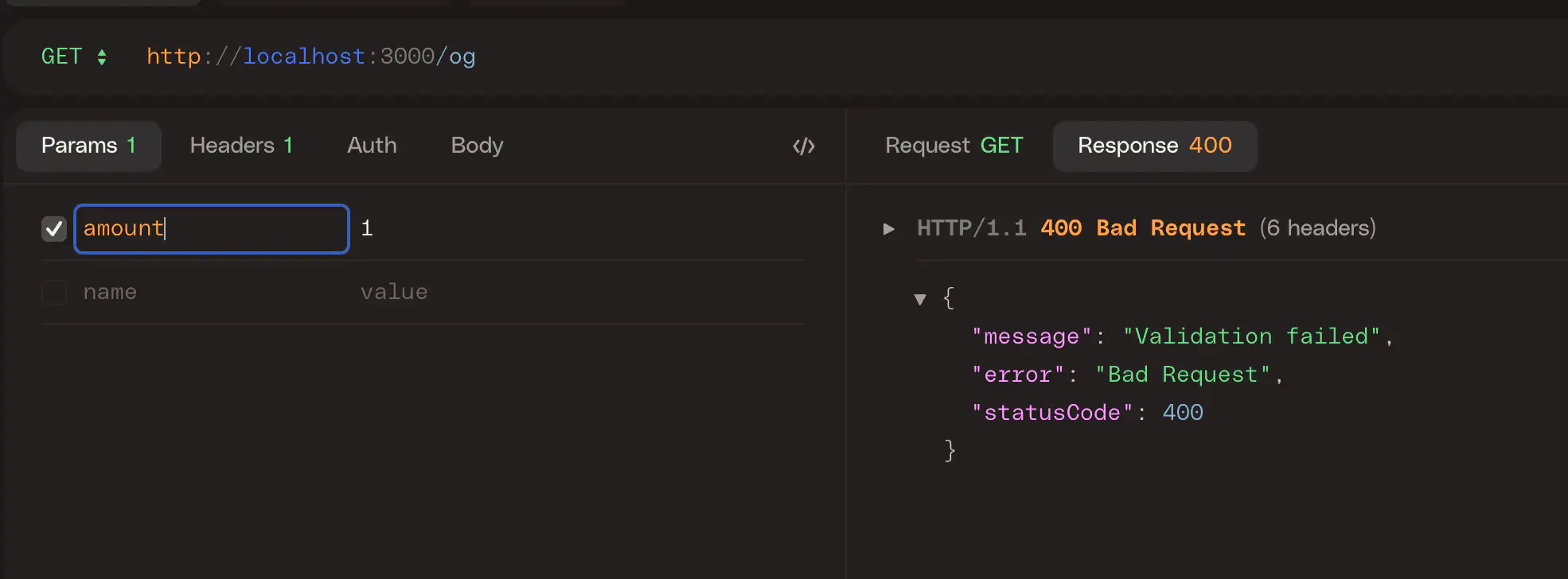

The query params trap

Unless you specify a DTO, there's no type validation, and your types will be completely wrong. Your TS code will assume it's a number anyways:

You'll find that the error handling is also pretty bad:

The basic error message from ValidationPipe is also super generic. It can be frustrating to work with if you don't know the implementation specifically:

Danger #4: Class Validator - Just use ZOD omg

Class Validator is the default validation library in NestJS, and it presents its own set of challenges.

Problem 1: Validators and types can diverge

When you write:

@ApiProperty()

@Expose()

@IsString()

logoUrl: string;You always need to make sure the type and the validators match. If the type is optional but not the validator, or the other way around, it can lead to issues:

// ❌ Type says optional, validator says required

@IsString()

logoUrl?: string;

// ❌ Validator says optional, type says required

@IsOptional()

@IsString()

logoUrl: string;It gets worse: null and undefined have different semantic meanings, and you need different decorators for each:

// Primitive values from DB: either present or null

@ApiProperty({ type: 'string', nullable: true })

@Expose()

@IsNullable() // Custom decorator you have to build!

@IsString()

routingCode: string | null;

// Relationships: either present or undefined (not from DB)

@ApiProperty({ type: BankAccountMetadata, nullable: true })

@Expose()

@IsOptional() // Built-in, but means undefined, not null

@Type(() => BankAccountMetadata)

@ValidateNested()

bankAccountMetadata?: BankAccountMetadata;The distinction between null (DB value doesn't exist) and undefined (relationship not loaded) is crucial, but class-validator treats them completely differently—and @IsNullable doesn't even exist out of the box.

Problem 2: Nested validation is confusing

@ValidateNested() requires @Type() decorator to work properly, but this isn't obvious:

export class CurrencyExchangeRate {

@Expose()

@ApiProperty({ enum: Object.values(currency) })

@IsIn(Object.values(currency))

target: currency

@Expose()

@ApiProperty({ type: 'number' })

@IsNumber()

rate: number

}

export class CurrencyExchangeResponseDto {

@Expose()

@ApiProperty()

@ValidateNested()

@Type(() => CurrencyExchangeRate) // Easy to forget!

rates: CurrencyExchangeRate

}And what happens if you don't add { each: true } to @ValidateNested() when validating arrays? The validation silently doesn't work as expected.

More issues raised by users:

- Validate nested objects using class-validator and nestjs

- class-validator#193 - @ValidateNested not working

Problem 3: Missing validators

@IsNullable() validator doesn't exist—you need to create it yourself:

// You have to build this yourself

export function IsNullable(validationOptions?: ValidationOptions) {

return ValidateIf((_, value) => value !== null, validationOptions)

}Same goes for @IsBigInt() and several other common use cases.

Problem 4: DTOs don't strip extra values by default

Using class-validator in a DTO requires you to check whether it removes extra values passed to it. Otherwise, you're serving unwanted values from your API:

// Without proper configuration, this DTO won't strip unknown fields

class CreateUserDto {

@IsString()

name: string

}

// Someone sends: { name: "John", isAdmin: true }

// Your API might pass isAdmin through to your database!Problem 5: When is validation actually happening?

Creating an entity with new Entity() doesn't validate anything! You need to explicitly integrate validation logic:

import { ClassConstructor, plainToInstance } from 'class-transformer'

import { validate } from 'class-validator'

export class Mapper {

static async map<T extends object, V>(

type: ClassConstructor<T>,

plain: V | V[],

): Promise<T | T[]> {

const entity = plainToInstance<T, V | V[]>(type, plain, {

excludeExtraneousValues: true,

strategy: 'exposeAll',

})

const validationErrors = await validate(entity)

if (validationErrors.length > 0) {

throw new Error(JSON.stringify(validationErrors, null, 2))

}

return entity

}

}Problem 6: The @Expose() tax

@Expose() needs to be added to all fields if you want your entities to strip out all values passed that aren't meant to be there. Miss one field? That field won't be mapped.

Problem 7: Project maintenance concerns

Class Validator has numerous unresolved issues on GitHub, and the project appears to have limited active maintenance. Building your production system on a library that may not receive timely security updates or bug fixes is a risk worth considering.

Danger #5: Swagger integration, or lack thereof

ApiProperty type inference

ApiProperty doesn't need a type specification for simple types, but complex types need explicit declaration:

// ✅ Works fine

@ApiProperty()

name: string;

// ❌ Won't infer correctly

@ApiProperty()

settings: ComplexSettingsType;

// ✅ Need to specify

@ApiProperty({ type: () => ComplexSettingsType })

settings: ComplexSettingsType;Nullable isn't straightforward

nullable doesn't come out of the box as you'd expect:

@ApiProperty doesn't work seamlessly with @IsNullable, and you need to specify the type in the decorator. This isn't documented well.

Object types are painful

Defining an ApiProperty that returns an object is surprisingly difficult.

Swagger types can drift from actual types

You always have a risk that your type isn't being recognized when it's complex, and also of your Swagger type and entity types going out of sync. This defeats the purpose of auto-generated documentation.

More issues raised by users:

Danger #6: Circular dependency hell

NestJS's module system can lead to circular dependency nightmares: The error messages are often cryptic and don't point you to the actual source of the problem. Debugging these issues can waste hours of development time.

Danger #7: OOP is a thing of the past

NestJS's reliance on classes is outdated. It's 2022 (now 2026 as I publish this. React move away 10 years ago now.). This pattern is not scalable and will cause you pain in the long run.

Choosing an alternative

If you're starting a new project and NestJS was on your radar, here are some alternatives worth considering:

Vanilla Express + TypeScript

Sometimes the best framework is no framework. Express has been battle-tested for over a decade and remains the most popular Node.js server framework. Combined with TypeScript and a few carefully chosen libraries, you get:

- Full control over your architecture

- No magic decorators or hidden behavior

- A massive ecosystem of middleware

- Easy to understand request/response flow

Pair it with Zod for validation and you'll have type-safe request handling without the decorator soup.

Next.js + next-safe-action

If you're building a full-stack application, consider Next.js with next-safe-action. This combo gives you:

- End-to-end type safety between server and client

- Input/output validation with Zod, Valibot, or any Standard Schema compatible library

- Powerful middleware system for auth, rate limiting, and logging

- Optimistic updates out of the box

- Form Actions support with stateful and stateless options

// Example from next-safe-action

'use server'

import { z } from 'zod'

import { actionClient } from './safe-action'

const inputSchema = z.object({

name: z.string().min(1),

})

export const greetAction = actionClient

.inputSchema(inputSchema)

.action(async ({ parsedInput: { name } }) => {

return { message: `Hello, ${name}!` }

})No decorators, no classes, just functions with proper type inference. The DX is excellent. It's actively maintained and there is no incentive to sell a course to learn it.

AdonisJS

AdonisJS is a full-featured MVC framework for Node.js that takes a more serious, Laravel-inspired approach. I haven't used it in production myself, but from what I've seen:

- First-class TypeScript support from the ground up

- Comprehensive documentation that doesn't upsell you

- Built-in ORM (Lucid) that's actually well-designed

If you really want to write 10x more code than needed using classes and MVC patterns, this is probably the best alternative.

This is only my opinion. The best framework is the one your team can use effectively. If everyone knows Express, stick with Express. If you're building a Next.js app anyway, next-safe-action is a no-brainer.

Conclusion: The unspoken cost

It looks simple because the docs show simplistic code examples, but once you're actually building something, NestJS can become a wasp nest.

Companies often don't hire developers with NestJS experience, and therefore all these issues occur repeatedly across the industry. If you're considering NestJS, make sure you have at least one person on the team with real-world experience, or be prepared to learn these lessons the hard way.

Good luck out there!